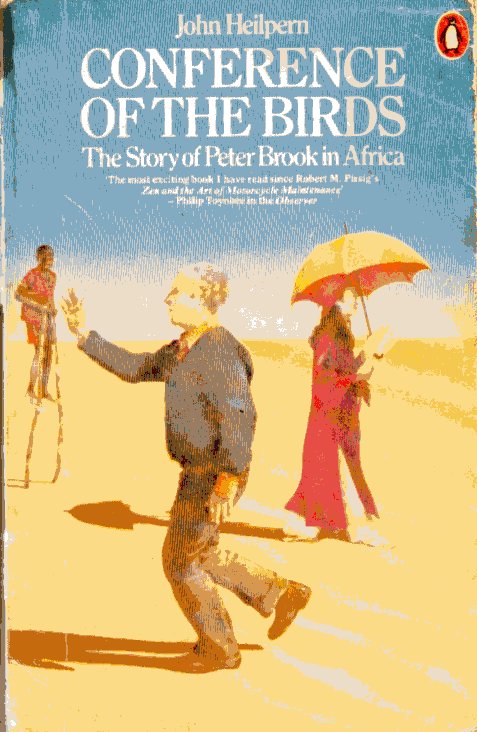

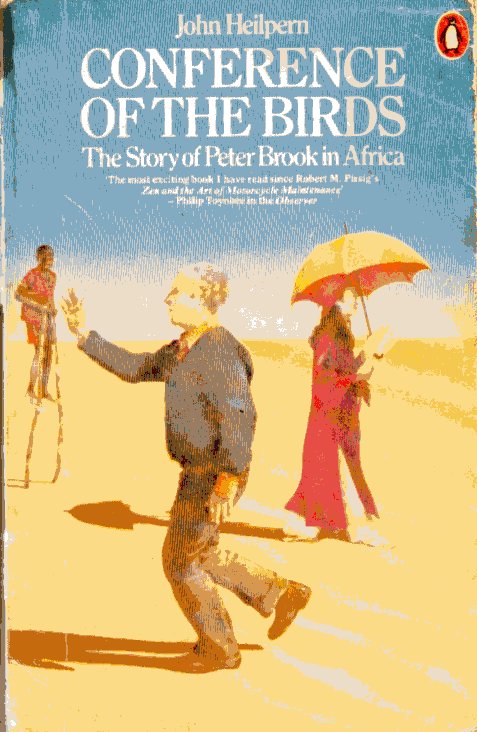

I’ve just re-read one of my favourite books – ‘The Conference of the Birds’ by John Heilpern. It’s a colourful and fascinating story, describing a journey through northern and western Africa made by British theatre director Peter Brook, with a troupe of actors, back in 1972/3.

John Heilpern has a great eye for detail and an infectious sort of curiosity about what goes on. The strange and talented mix of international actors are brilliantly brought to life, as are their many performances.

There’s some healthy scepticism. (By the third chapter, Heilpern has managed to tell us, “I like actors but sometimes they don’t know their arse from their elbow.”) And the writing is very funny. Nearly every chapter makes me laugh out loud, at something.

As well as enjoying the writing, I like the story. The book describes a journey in search of a theatrical experience which Peter Brook himself cannot easily define.

Along the way there are moments of magical inspiration, others of complete failure.

There’s a lot of plain, hard slog.

Everyone seems bewildered, at least some of the time. (At one point Heilpern says, “Nobody knew what they were there for or where they were going.”)

There are trials and errors, risks taken, flashes of good and bad luck, and completely unexpected moments of freedom and delight.

So, although it is all writ large (30 people travelling 8,500 miles through deserts, mountains and tropical forest) it feels as if Brook and his actors are journeying through the things that anyone following an artistic dream (with its madness, desperation and beauty) will end up experiencing.

I think that’s why the book grabbed me when I first read it, as a young man, curious about what it might mean to set off on an artistic journey. And it’s probably why it still grabs me some years later…when there’s no turning back!