HOW TO WRITE A FUNNY PICTURE BOOK

Posted on 8th June 2024

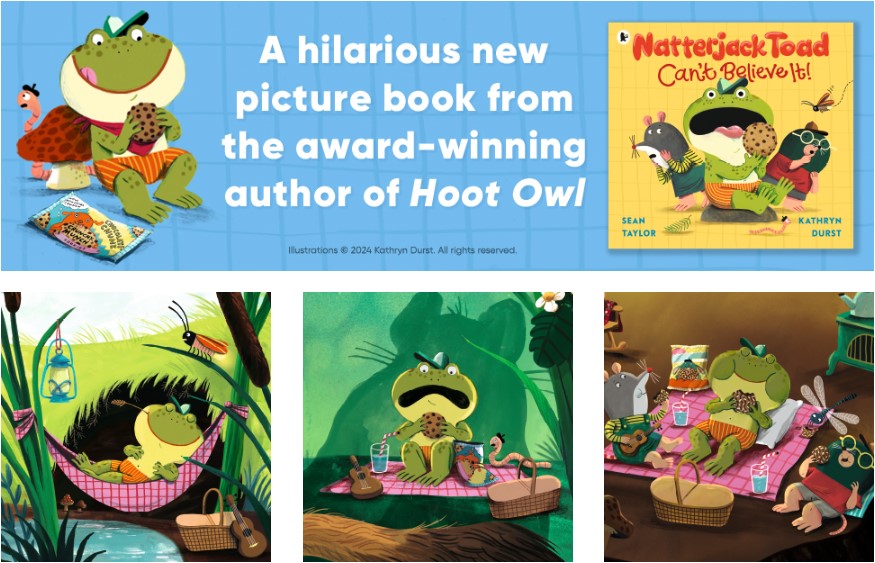

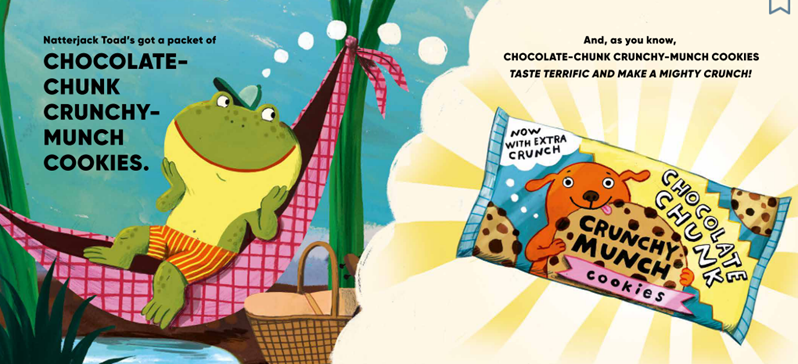

My latest picture book is about new friends, unwelcome predators, and a packet of very noisy biscuits. It’s NATTERJACK TOAD CAN’T BELIEVE IT! (illustrated with panache by Kathryn Durst.) And to celebrate its arrival, I’ve come up with some tips on funny writing for young readers. You’ll find the tips one by-one on Instagram (here). Or you can read the whole shebang below…

There are seven rules for writing a funny picture book. Unfortunately, nobody knows what they are.

Like a lot of jokes, the above has truth running through it. There won’t ever be a set of instructions for doing funny writing for young readers. You can’t treat it like assembling a chest of drawers. And if you tried arriving at comedy from a set of instructions, it would work against the spontaneity, unexpectedness, and (you might say) wildness which often sparks what’s funny.

The British writer and comedian, Barry Cryer, summed this up nicely by saying, “Analysing comedy is like dissecting a frog. Nobody laughs and the frog dies.”

So is there any help I can offer to those who want to write funny (or funnier) picture books?

What I can do is look back at NATTERJACK TOAD CAN’T BELIEVE IT! now the book’s written, and try to spot some of the things going on in terms of the comedy. Read on for those things. And here’s hoping they’ll provoke creative (and funny) thoughts of your own.

[1] EXAGGERATION

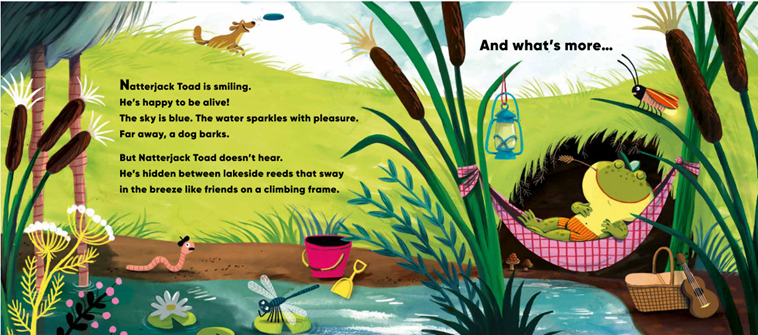

The water sparkles with pleasure.

Lakeside reeds that sway in the breeze like friends on a climbing frame.

This isn’t laugh-out-loud funny. But I’m exaggerating the imagery right from page one. It establishes an engagingly tongue-in-cheek narrative voice. And because everything is exaggeratedly perfect, when the trouble comes (as it must, in some way, in a story) it’s all the more comical.

[2] LANGUAGE

There’s humorous delight in the language here. It’s in the music of all those crunchy CH sounds. And there’s linguistic funniness in pastiching the ubiquitous language of advertising, with its catchy/corny slogans.

[3] SLAPSTICK DISASTER (physical or otherwise)

This isn’t Stan Laurel being hit on the head by a falling ladder, but it’s the emotional equivalent. Everything is fine. Everything is even finer than fine. Then it comes crashing down. Children find that funny. We all do (probably because we recognise it as one of life’s ever-repeating dynamics!)

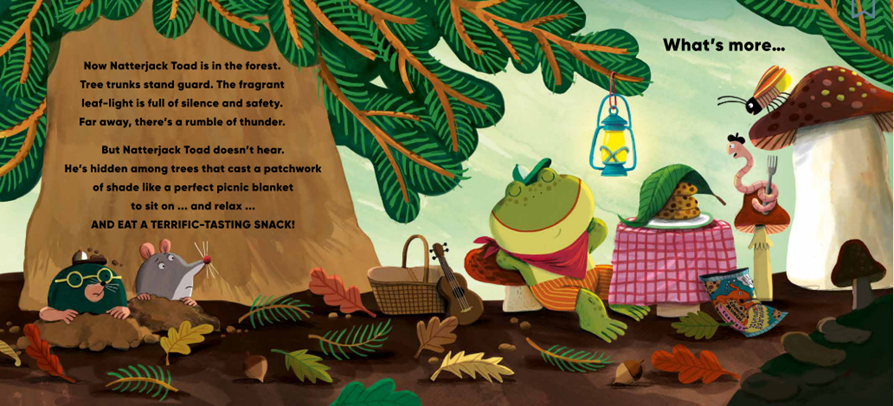

[4] REPETITION

We’re in the middle of the book now. The comic patterning of the opening spreads is repeating for a third time. And I’ve written the exaggerated imagery LARGER each time it comes around. So both the funniness and the expectation that something’s going to happen are growing as the text repeats and the pages turn.

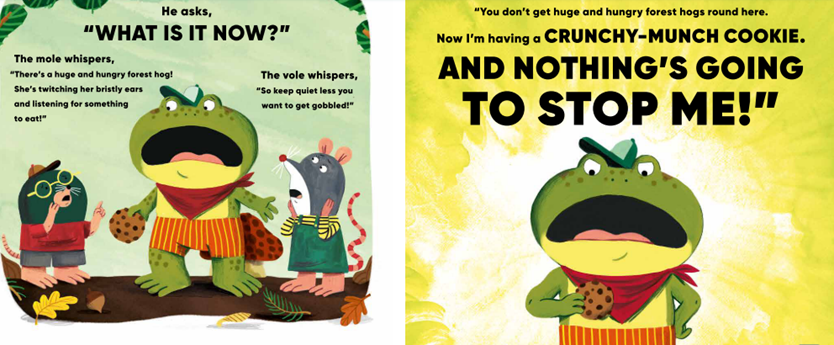

[5] STRONG EMOTIONAL REACTIONS

In the silent movies of the 1920’s (my favourites are the ones made by Buster Keaton) the slapstick incidents themselves are hilarious. But watch carefully and you realise there’s almost as much funniness in the strong emotional reactions of the characters. It can be wonderfully comic, seeing someone consumed by love, hilarity, pain, frustration or, as here, anger!

[6] TROUBLE

Natterjack Toad is doing what he’s been warned not to do! So we have a strong sense of trouble coming. I’ve mentioned two classic elements of slapstick comedy: the disaster and the strong emotional reaction. Here’s a third: the anticipation of trouble. It’s another thing that can make children fall about laughing.

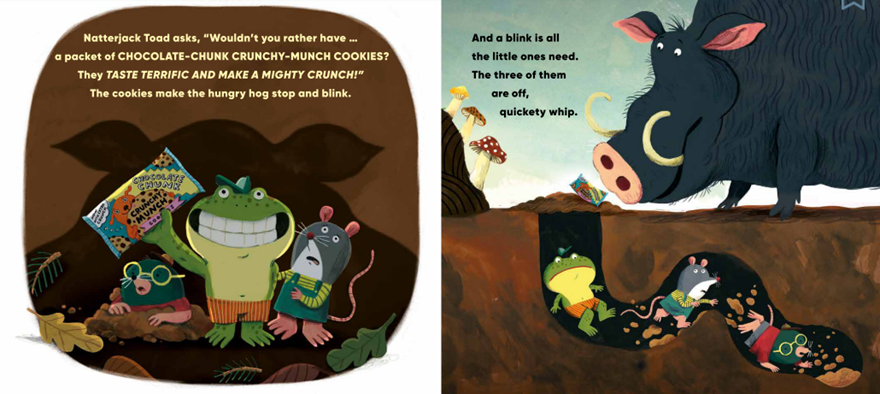

[7] QUICK-WITTEDNESS

And there’s comic delight in a main character outfoxing a fox (or, as in NATTERJACK TOAD CAN’T BELIEVE IT!, out-hungry-forest-hogging a hungry forest hog.) The plot twist that sees a much-loved protagonist make a smart escape may lead to a warm sort of laughter. It’s the laughter of resolution. We recognise quick-witted escapes from trouble as one of life’s repeating dynamics, just as we recognise falling off a bicycle into a duck pond.

There you are. Have I named the seven rules for writing funny picture books, AFTER ALL?

Not likely! What I’ve come up with aren’t rules. They’re just seven comic writing elements that I can spot, looking through NATTERJACK TOAD CAN’T BELIEVE IT!. Someone else might read the book and come up with a whole different set. Pick up other picture books, and you’ll probably soon have 777 other comic writing elements that work as well.

And maybe it’s daunting to be told there’s no neat set of rules for writing a funny picture book. Or maybe it’s freeing to know it’s a dance you can do in umpteen different ways!